By Menachem Z. Rosensaft

How will present and future generations of Jews and non-Jews around the globe, born decades after the end of World War II, come to terms with the Holocaust, the systematic annihilation of 6,000,000 European Jews at the hands of the Third Reich and its multi-national accomplices?

As the survivors of the Hitlerite “Final Solution of the Jewish Question” fade from the scene, and as their children and grandchildren – the witnesses’ witnesses – themselves reach middle age and beyond, Holocaust  remembrance is undergoing a gradual yet very much perceptible transformation. According to one disturbing recent survey, 41% of American adults, and 66% of American millennials, do not know the significance of Auschwitz. According to another poll, one in five young adults in France between the ages of 18 and 34 said that they had never even heard of the Holocaust.

remembrance is undergoing a gradual yet very much perceptible transformation. According to one disturbing recent survey, 41% of American adults, and 66% of American millennials, do not know the significance of Auschwitz. According to another poll, one in five young adults in France between the ages of 18 and 34 said that they had never even heard of the Holocaust.

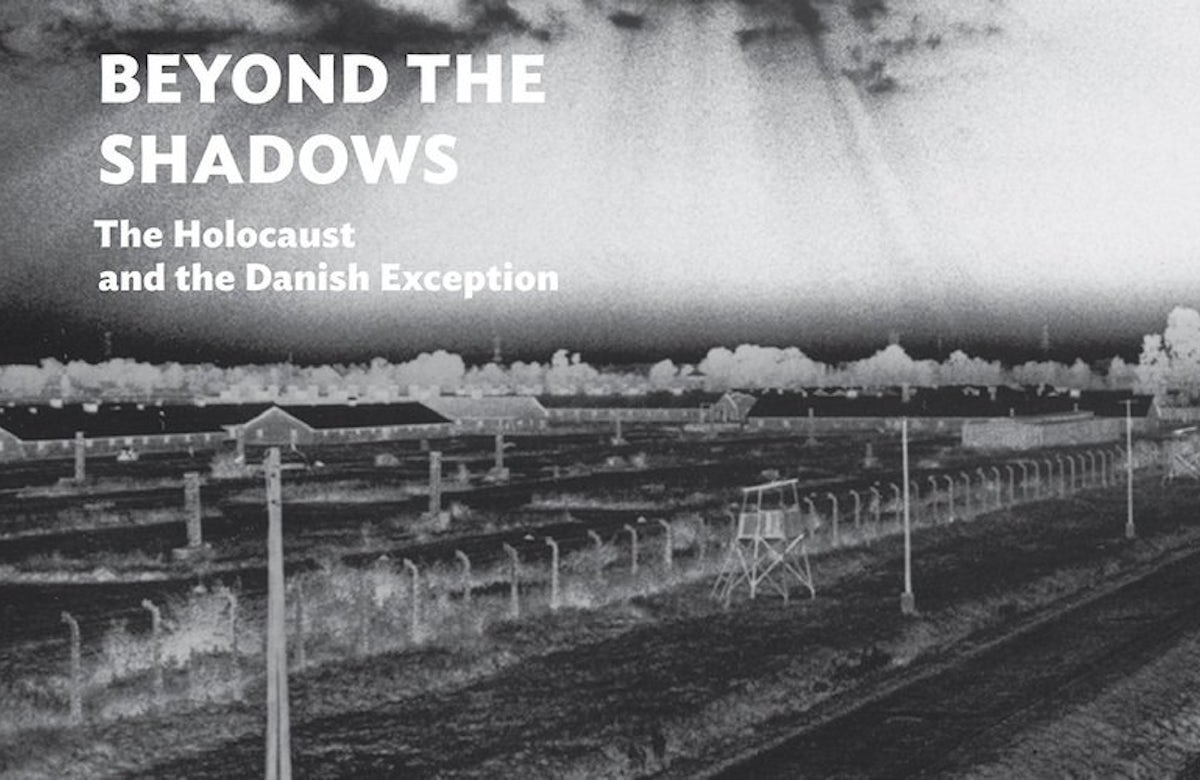

One way of conveying the enormity of the Holocaust is by literally bringing its imagery into people’s homes. This is what photographer Judy Glickman Lauder has accomplished in her superb book, Beyond the Shadows, The Holocaust and the Danish Exception, published by the Aperture Foundation. This beautifully produced volume combines ethereal photographs of the death camps and other sites where the genocide of European Jewry occurred with portraits of Danes who risked their lives to successfully rescue most of their Jewish neighbors and friends.

In a poetic prologue, the late Holocaust survivor and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Elie Wiesel captures the essence of Glickman Lauder’s photographs. “It’s as if they infiltrate the entire universe, where a last gaze is fixed, a last breath taken. Shadows, enormous and evanescent. Shadows that suffer … Shadows of nocturnal memories. It is frightful to penetrate them since, in the blink of an eye, there is danger of drowning in them.”

A blurred image of the railroad track leading from Warsaw to the Treblinka death camp, followed by another of an eerie railroad crossing at Treblinka with ghost-like white trees in the background. Photographs of the stark present-day interior and exterior of the barracks at Auschwitz-Birkenau force the viewer to imagine what this place had been like more than 75 years ago when it had been overwhelmed by horror and unspeakable suffering. A surrealistic depiction of the famed “Arbeit macht frei” (work makes one free” gate at Auschwitz is followed by the same legend at the Theresienstadt and Dachau concentration camps, a reminder that the Nazi German abuse of language was not confined to any one place.

A shadowy human shape, perhaps that of the photographer, can be seen against an Auschwitz crematory oven, next to an observation by historian Yehuda Bauer: “… some of us ask where was God, and others ask where was Man?”

And then there are photographs taken in Denmark, filled with the knowledge that good could – and in rare instances did – prevail, interspersed with tombstones at the Jewish cemetery in Warsaw that seem to be stand-ins for long-dead accusers. Then there is the wall constructed from desecrated Jewish gravestones in Krakow, followed by a child’s face, from a Theresienstadt poster, against the background of the Old Jewish Cemetery in Prague.

In an introductory essay, Holocaust scholar Michael Berenbaum juxtaposes Glickman Lauder’s photographs of shoes left behind by Jews about to be gassed at Auschwitz-Birkenau with a poem by Moses Schulstein that exclaims: “We are the shoes, we are the last witnesses … and because we are only made of fabric and leather, and not of blood and flesh, each one of us avoided the hellfire.”

“The images,” writes Glickman Lauder about the photographs she took at Auschwitz in 1988, “feel out of time – in a way that is mystical and ghostly. For me they express a world turned upside down and inside out. . . . I felt I was photographing both – the visible evidence of what had transpired and the void, the emptiness . . . the absence of those who had died there.”

Beyond the Shadows is a masterpiece that deserves to be experienced by all who are willing to immerse themselves in Judy Glickman Lauder’s reflections of what Auschwitz, Treblinka and Theresienstadt represent, and to enter through her photographs the unfathomable universe of what Elie Wiesel aptly termed the “kingdom of night.”

Menachem Z. Rosensaft is General Counsel of the World Jewish Congress, and teaches about the law of genocide at the law schools of Columbia and Cornell Universities.