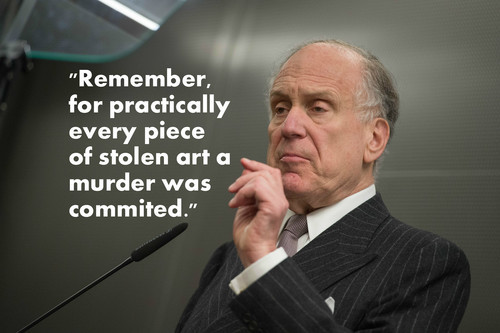

Transcript of the lecture delivered by World Jewish Congress President Ronald S. Lauder at the Kunsthaus Zürich on 2 February 2016.

Ronald S. Lauder:

Thank you Herbert for your kind words, and your very accurate assessment.

Honored guests, ladies and gentlemen, thank you for joining me tonight at a location that is so closely related to art, but on a topic that is not easy to discuss.

It is not easy to discuss because of where we are, not easy because it involves Switzerland itself, along with the rest of Europe, which has based its postwar success on upholding the law, following the rules, and moving on from the horrors of World War II.

It is not easy to discuss because of where we are, not easy because it involves Switzerland itself, along with the rest of Europe, which has based its postwar success on upholding the law, following the rules, and moving on from the horrors of World War II.

And it is certainly not easy because a crime committed 80 years ago continues to stain the world of art today. I must confess this talk is unusual for me.

Although I’ve been working on the problem of art restitution for more than a quarter of a-century, since 1990, I’ve only spoken about this topic in public once before.

That’s because I always felt that art restitution should be done quietly.

Tonight is different for two reasons. First, because of the Gurlitt collection, and second, because that collection is coming to Switzerland.

Everyone in the art world and probably everyone in this room was surprised by the discovery of the Gurlitt collection in Munich two years ago.

We all suspected that much of this art was probably stolen from Jews because Cornelius Gurlitt was the son of Hildebrand Gurlitt, one of Hitler’s personally appointed art dealers.

Over a thousand works of art don’t just “show up” in someone’s home, especially someone who never seemed to work a day in his life.

But my surprise turned to shock when I learned that the collection would go to one of the world’s great museums, the fine arts museum in Bern.

This made absolutely no sense to me. Why in the world would the Bern museum want to get anywhere near a collection that was probably stolen from Jewish homes by the Nazis?

You already heard Mr. Winter explain his disappointment that after two years of investigation, a German government task force determined that only five pieces were wrongfully taken from Jewish owners.

The reason for this, I believe, is very simple.

The art in the Gurlitt collection were mainly drawings and prints. There were very few paintings.

The Nazis kept excellent records of the art they stole. The paintings and sculptures were well documented.

But all the rest were usually categorized simply as “10 drawings”, or “5 prints”, nothing specific, making these works hard to trace.

So why, I wondered, would a museum want these works that may very well have been stolen from Jewish homes?

Would people even want to go and see these pieces?

If it had been called the Heinrich Himmler Collection instead of the Hildebrand Gurlitt collection would any museum ever want these works of art?

That may sound harsh but in terms of stolen art there really isn’t much difference between Gurlitt and Himmler.

Hildebrand Gurlitt, along with Alfred Rosenbert, Kajetan Muhlmann and Karl Haberstock, were all indirectly part of the Nazi machine. All four of these men were chosen by Adolf Hitler to steal Europe’s art.

They told the Nazis which homes to go to for the best works of art.

And once taken, they all knew where this art – the ones not taken by Nazi officials – could be resold. These four men – Gurlitt, Rosenberg, Muhlmann and Haberstock - along with a few others, were given a license to steal and then sell works of art owned by Jews.

And although some of this art was labeled “degenerate” by the Nazis and taken from museums, much of it was simply taken from private homes.

Hitler’s art dealers are at the very center of the greatest theft in history.

And they all personally benefitted from the suffering of others.

That is why I make the comparison between Hildebrand Gurlitt and Heinrich Himmler.

Because of the Bern museum’s decision to take Gurlitt’s collection, I started to look at Switzerland’s role in what many people now called “lost art.”

Can we please – once and for all – stop using the term “lost” art? None of this art was “lost.”

It was not lost the way you might lose your wallet, unless your wallet was taken at gunpoint by a robber.

These works were taken from the walls of people’s homes, they were robbed the way robbers take whatever they want.

“Lost art” sanitizes the crime. From now on let’s refer to this as stolen art… not lost art.

These works were stolen by Nazis. But they were also stolen by governments that looked the other way.

There were museums that were all too willing to put these stolen paintings on their walls, and these museums should have known better!

Let me point out the hard truths that no one likes to talk about here.

Shortly after the Nazis took power, they introduced the Nuremburg laws in 1935.

These new laws placed severe racial restrictions on Jews.

Jews were no longer allowed to be citizens of the Reich, and they were denied basic political rights.

30,000 German Jews immediately lost their jobs in government, in universities, in corporations.

Jewish doctors could not treat Aryan patients, Jews who owned newspapers, publishing houses and department stores, lost everything.

Jewish doctors could not treat Aryan patients, Jews who owned newspapers, publishing houses and department stores, lost everything.

That means they had to sell their possessions in order to survive. Everyone knew that the Nuremburg laws forced Jews to sell their furniture, their rugs, and their paintings. Everything for 5 percent of what it was worth.

That is why today Raubkunst and Fluchtgut must be treated the same way.

The literal English translation for Raubkunst is "Nazi plunder" or "Nazi looted art", whereas Fluchtgut deals with art and other items that Jews were forced to sell at low prices in order to survive.

But could it possibly make any difference if a painting was taken off the wall by a Nazi – or if its Jewish owner was forced to sell that same painting to one of Hitler’s art dealers for almost nothing?

Is there any difference in the outcome for the victim’s families?

The director of the federal office of culture, Isabelle Chassot, stated in an interview last fall: “only Switzerland makes the distinction between Raubkunst and Fluchtgut.

The term “art losses that were caused by Nazi-persecution” would be much more precise.”

I fully agree with her. Raubkunst and Fluchtgut are, indeed, the same! But why isn’t this the official policy?

After the Nuremburg laws forced these sales, many countries took advantage, and, yes, that included Americans as well.

But at the very center of it all, Switzerland quickly became a major center for Nazi stolen art.

In 1937 Joseph Goebbels presented the famous Entartete Kunst show. The Nazis pulled the paintings off museum walls by Jewish and modern artists that did not fit their tastes. At the top of their list were the expressionists, the cubists, and Jewish artists like Marc Chagall.

But German officials quickly realized these pieces could be sold for badly needed foreign currency, money that could be used to finance their war effort.

Since many foreigners did not want to buy from them directly because it didn’t look right.

The Nazis just needed a middle-man.

They found the perfect middlemen in people like Theodor Fischer, one of Switzerland’s foremost art auctioneers.

In 1939, Fischer set up the grand hotel auction where he lived in Lucerne, attracting some of the world’s top art dealers, collectors and museum directors.

The 126 paintings on the block included:

Franz Marc’s “Three red horses”, Gauguin’s “Landscape of Tahiti with three female tigers”, Picasso’s “The harlequins”, and works by Beckmann, Heckel, and Kirchner.

Everyone in the art world knew what these paintings were. Everyone knew where the paintings came from and how they got there.

End everyone knew why they were so cheap.

In some cases, this entire pretense of this auction was so transparent, it was downright embarrassing. For his part, Theodor Fischer backed up the Nazi distaste for these artists with his own negative commentaries.

One major collector – Marianne Feilchenfeldt – saw her painting – Cathedral of Bordeaux by Kokoschka – the same painting she had donated to the Nationalgalerie in Berlin, on the auction block.

A large percentage of the works were purchased by Swiss collectors and museums.

The Nazis set up some rather complicated schemes to bypass the laws of propriety, with Switzerland at the center of it.

Many of the great auction houses in Europe had closed during World War II, leaving neutral Switzerland to pick up everything else as Europe’s main auction center.

It was, in fact, not just convenient to be neutral in World War II.

It was very lucrative as well. Make no mistake, Theodor Fischer and Switzerland were not alone.

Much of Europe became a thriving market for stolen art.

But as bad as all of this was, the story gets even worse.

After the war and the unconditional defeat of the Nazis, Swiss banks, museums and private collectors

Conveniently challenged the validity of anyone who tried to retrieve Jewish property. Between 1933 and 1947, Theodor Fischer held 47 auctions, so you see it is quite clear that auctions of this art continued well after the war ended.

However, it seems that Fischer had the Swiss court on his side. In a very strange decision in 1948, the Swiss federal court held that both Fischer and arms merchant and art collector, Emil Buhrle, had acted in good faith in their purchases, but they were still told to return some of their art acquired during the war.

Then the Swiss federation actually reimbursed Fischer for the stolen art he was forced to return.

It has been said that according to the Swiss, “good faith” is when

One closes his eyes and disregards any information that could be troublesome.

In 1997, I was asked to join the Volcker Commission that audited Swiss banks. The commission learned how banks that are the foundation of this country abused every possible tactic to keep the deposits made by desperate Jews before and during the war.

After 1945, if an heir tried to retrieve funds deposited by a dead relative, the banks demanded proof like official death certificates.

How unfortunate that Auschwitz and Treblinka and Theresienstadt did not issue death certificates.

We also know that bank vaults where Jews placed art and jewelry were opened and looted because murdered Jews failed to pay their fees.

Unfortunately, an inventory of the contents of these boxes was difficult to obtain.

We will never know what was in them and what was stolen.

Mahatma Gandhi once said: “There is a higher court than the courts of justice and that is the court of conscience. Conscience supersedes all other courts.”

Keep this quote in mind tonight as I talk about the art that was stolen from Jews by Nazis and remains stolen more than eight decades later.

Yes, humanity seeks justice. But not just the justice the lawyers may give us.

I’m talking about the justice of humanity and fairness.

Here is something I believe strongly: in the back of all of your minds you know that what I am saying is true and you know these paintings should be given back to their rightful owners!!

You know this because if you put yourself in their place.

If something that you cared deeply about was taken from you, you would want it back.

Nazi crimes have always been quite clear.

But for many people and even major museums, when it comes to the question of the art, stolen art, something strange happens. People seem to look the other way.

We are told that, somehow, stolen art is more complicated. Somehow, its victims are not really victims, somehow, it’s ok when world famous museums have Nazi looted art on their walls. Somehow, if it’s in a public museum, the crime is cleansed. Some others say “let’s leave stolen art to the courts and the courts will provide justice based on law.”

Here’s the problem with that: the laws were not drafted with a crime like the Holocaust in mind.

Before 1945, no one could have imagined such a crime. Remember that concept that Gandhi called conscience.

Keep listening to your conscience as I explain why this problem should have been solved decades ago and why individuals and museums and whole countries

Dragged their feet so there would be no resolution. Some museums say they acquired these pictures legally, or they didn’t know.

There are far too many examples of this, but two stand out for me. The Jaffe family owned a large art collection in Nice, France.

In 1943, the Vichy government held what was called a “Jew auction”, which meant that all their paintings were sold for almost nothing.

They were then resold at market value and the officials of the Vichy government put the money directly into their pockets.

The collection eventually spread around the world, and one painting - “Dedham from Langham” by John Constable - was purchased by an art dealer in Switzerland in 1946.

The painting was finally located in 2006 at the fine art museum in La Chaux-de-Fonds in Switzerland, near the French border in Jura.

The Jaffe family retrieved several of their other paintings from various countries, because the ownership was quite clear. All institutions in various countries cooperated except one: the Chaux-de-Fonds Museum.

Here, the museum suggested that since the claims were against the Vichy government, the family should go to France for their money.

This decision, I believe, shows a troubling lack of shame. As of today, “Dedham from Langham” still hangs in the fine arts museum in La Chaux-de-Fonds.

Remember the question of conscience? Do you think this is right?

In another case, the Meyer family of France lost its art collection in 1941 in a similar theft.

In 1952, their painting “shepherdess bringing in sheep” by Camille Pissarro, was found in the possession of a prominent Basel art dealer, Christoph Bernoulli. When the Meyer family attempted to negotiate its restitution, Mr. Bernoulli, offered to sell it back to them, but at full market price.

Does that sound right to you?

When the Meyer family brought legal action against the dealer, the Basel court held that the Meyer family could not get it back.

Why?

The court said the Meyers could not prove Mr. Bernoulli purchased the painting in bad faith. Case closed.

The painting resurfaced again 60 years later, in 2012, in, of all places, the Fred Jones Museum at the University of Oklahoma, where it was donated as a gift.

The family continues to fight for this stolen painting, a painting that was really stolen twice.

Herbert Winter mentioned the Washington Principles. Let me explain exactly how they came about.

Sixteen years ago, in 1998, Stuart Eizenstat and I knew that one international standard was needed to govern all stolen art: we developed that standard and it’s called the Washington Principles.

Switzerland has endorsed the Washington Principles. The major Swiss museums have endorsed the Washington Principles.

The Washington Principles provide the standard when it comes to stolen art.

Everybody who endorses the Washington Principles commits to find fair and equitable solutions in cases of stolen art.

I strongly believe that because Switzerland signed the Washington Principles, we can all work together and find a fair and equitable way to move forward.

How does a country find fair and equitable solutions?

I believe there are six essential requirements:

First: stolen art must include all art losses caused by Nazi-persecution. That’s the Raubkunst and Fluchtgut that I spoke about earlier.

All of these losses were caused by the Nazis and they were aided by local governments throughout Europe.

Second: provenance research must be conducted pro-actively. It’s not right that the victims have to prove that they own their paintings…

The museums must be obligated to research their paintings.

Third: sufficient funds must be provided for provenance research.

Every country that endorsed the Washington principles automatically makes the commitment to provide sufficient funding for this research.

The director of the Federal Office of Culture recently announced that an amount of 500,000 Swiss francs will be available for provenance research this year. This is an important step.

The director of the Federal Office of Culture recently announced that an amount of 500,000 Swiss francs will be available for provenance research this year. This is an important step.

It shows that the federal office of culture is committed to this task.

The political decision to support public and private museums with sufficient funding for provenance research must be taken and implemented now.

Fourth: there must be complete transparency on all aspects of provenance research: by means of one centralized internet database. A centralized database should be open for all museums, collectors, art dealers and historians, to publish the results of their provenance research.

This will facilitate the search for stolen art. It will facilitate the exchange of information on stolen art. And it will help victim’s families find the relevant information on stolen art.

Fifth: One independent commission must be established. This commission will provide proposals for fair and equitable solutions in cases of lost art to museums and victim families.

Museums may have conflicts of interests when it comes to decisions on stolen art.

This should be taken to an independent commission and I urge the Swiss museums to create one now.

And finally, the sixth point that cannot be overlooked: too often, auction houses receive pieces they know are stolen art, but they ignore it.

A buyer comes along and spends a great deal of money in good faith that the auction house did its due diligence.

Many citizens of Switzerland purchased art in auction houses not knowing the background and have Jewish art stolen by Nazis on their walls today.

We are now retrieving records from auction houses over the past 20 years, so buyers will be able to check a data base for the history of anything they purchase.

But, honestly, I don’t have an answer for someone who bought a painting in good faith 30 years ago and now finds that it is a stolen piece of art. I do know that in the case of the Bern museum of fine arts they are wrong.

And the actions of many auction houses over the years are wrong as well.

What we need to do now is stop this from happening in the future.

Why is this urgent in 2016?

Remember, for practically every piece of stolen art a murder was committed.

More than 70 years after the end of World War II and the holocaust, an end to this problem is long overdue.

I have laid out six essential requirements that would begin the process of putting these ghosts to rest, once and for all.

People have been told that determining the provenance, checking on the history and ownership of a painting, is a complicated process. That’s not true.

If people are honest, if they really want to solve this issue, if they have a conscience, then they should stop hiding behind excuses.

I know everybody here wants to solve this problem.

I believe all of Switzerland wants to close this chapter.

Switzerland endorsed the Washington Principles.

The Swiss museums endorsed the Washington Principles.

That is a strong statement in favor of the victims of Nazi persecution.

Switzerland has taken an important first step by providing money for research.

This country, among all countries, should make sure this happens.

Switzerland can now set the gold standard for finding fair and equitable solutions for stolen art.

It is time.

Ladies and gentlemen,

We cannot go back and change what has happened. All we can do is stop the continuation of this crime.

No one is telling an individual to give back anything they purchased in good faith.

But they should at least know the history of ownership of anything they have in their homes.

And museums and auction houses must, finally and completely, have the responsibility to do the provenance research on all of their work!!

Art historian holger Klein has said: “The ghosts have come back to haunt us, and they will continue to haunt us until there is restitution.”

After more than 70 years don’t you think it’s time to put these ghosts to rest? I believe it is time.

Ladies and gentlemen: it is, in fact, long past time.